Mount St. Helens National Monument

Washington State

I have seen many sights in this world that have inspired me with a sense of wonder at the incredible complexity and power of God's creation but I have never witnessed anything that has the visual impact of the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument.

To the wanderer who has come to this special place, it is many things at the same time; it is majestic, frightening, beautiful, haunting, awe inspiring, sad, hopeful, and inspirational. Even as you gaze upon this scene with your own eyes, you are left with a very real sense that part of it maintains itself beyond your comprehension and continues to escape you.

I was so inspired and impacted by my visit to this park that I talked about it with my family almost without end for quite some time. That is why I have created this web page. To try to share with you some of the feelings I experienced when visiting this incredible and almost spiritual place. If you can look upon a place like this and still doubt the presence of a real God who created it all, then I guess I'm not sure what exactly it would take to convince you that He exists. For me, it was an amazing tribute to His power and the complexity of His creation.

I hope you will have an opportunity to visit this national monument some day. Hopefully my pictures and words will somehow encourage you to make a trip to visit this place. Unfortunately, I think no words or pictures can adequately portray the experience associated with visiting such a place. However, I'll try to give you at least a glimpse of this incredible place.

Mount St. Helens National Monument

This sign marks the entrance to the national monument. It is beautiful country with rolling hills and lush green forests. Prior to the blast that occurred on May 18, 1980 at Mount St. Helens, all of the mountains within this range were covered with evergreens of various species; some of them were 150 to 200 feet tall. It makes you feel very small indeed to walk through such a forest.

Viewing Mount St. Helens from the Southeast

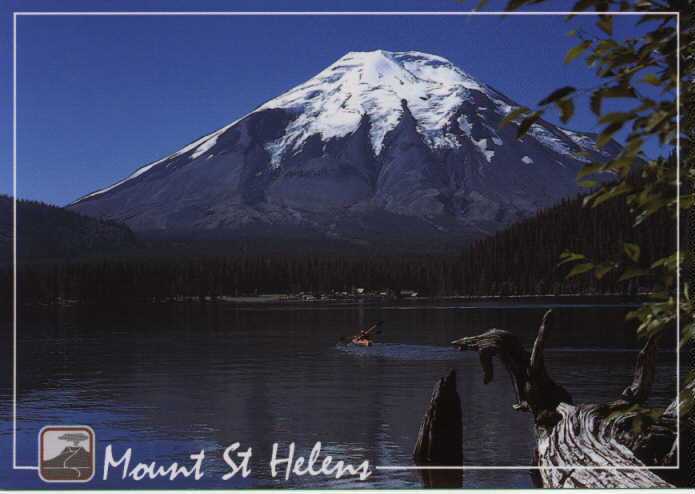

I decided my first visit to St. Helens would be from the southeast side of the mountain at a place called Lahar Viewpoint. I left interstate I-5 and took highway 503 east, just north of Vancouver, Washington. After driving for about 30 miles I entered the property set aside as part of the national monument. The south side of the mountain was uniquely spared from the devastation that took place in more than 180 degrees from the west side of the mountain, around to the north and even to the east. At Lahar Viewpoint, the mountain appears to be intact. However, you are actually looking at the rim of the crater that is clearly visible from the north side. The highest peak of the crater that is now Mount St. Helens is at 8,365 feet in elevation. However, prior to the blast in May of 1980, St. Helens towered to a mountain top peak that was at 9,677 feet. Thus, when the avalanche and subsequent blast took place, the mountain lost 1300 feet of its height in a matter of minutes. The picture below was taken as I approached Lahar Viewpoint. I had just stopped at the Ape Cave visitor center but declined to visit the cave in the interest of time. Ape Cave is a lava tube that you can explore (requires warm clothing and flashlights). It was most likely formed over 3000 years ago when St. Helens experienced a more typical volcanic lava flow. Such was not the case in May of 1980. I purchased my pass to visit the monument and continued on my way. You are looking at the southeast side of the mountain in this photo. Notice how thick the woods are here. This is the type of forest that was present on the north side of the mountain as well. That will be an important fact to keep in mind when you see what the north side looks like today. The trees here are amazingly tall! Look at the one on the far right; I couldn't even fit it all in my photo! (compare it to the car for size).

Another beautiful scene on the way to Lahar Viewpoint. This spot shows a very old lava flow that occurred long before the May 18, 1980 event. Notice the gray color of the volcanic material in the trench. The lava flows I looked at varied in color from light gray to black. Apparently the color is indicative of the type of flow that occurred and the rate at which it moved. My understanding is that the flows that occurred here thousands of years ago were more typical lava flows; slow moving rivers of red-hot rock. The flows that occurred during the 1980 eruption were called pyroclastic flows and I'll say more about that later. Frequently, the flows leave channels that are later occupied by water run-off from the mountains.

Lahar Viewpoint

This is the view of Mount St. Helens from the Lahar Viewpoint. You are looking at the southeast corner of the mountain. There was some damage near the northern most portion of the area (right hand side of this photo) due to avalanche and some of the pyroclastic flow coming into this area. However, immediately behind me there were many trees that managed to escape the devastation. Further south of this location, the woods are thick and green.

This is a close-up view of the northern most portion of the base of St. Helens (as viewed from the southeast). You can see how barren the plain below the mountain is and yet there are some very old trees on the far right hand side of the photo that have been spared. The trees on the right are in the 100-200 foot height range.

Lava Canyon

My next stop was one mile further north at a place called Lava Canyon. This lava flow area was believed to have been created by Mount St. Helens some 3500 years ago. Stream erosion has carved very deep channels into the the lava deposits in this region. The park service has a convenient parking area located about 1 mile above this canyon. I parked my rental and took off down the trails to see the lava flows. Of course the lava flows cooled off thousands of years ago but the rocky remnants left behind have created a beautiful natural environment for many different types of animals. Much of this area was covered with material from subsequent mudflows and other eruption deposits. During the 1980 event, a mudflow came through this area that removed some of the older deposits and revealed the beauty of this site. It seems that the mudflows will either deposit additional material (if they are moving slowly) or they will strip away or etch away any lose material (if they are moving fast enough). Apparently the 1980 mudflow that came through this area was moving fast. Take a close look at the upper right hand corner of this photo to get some idea of the scale of this place; that's two people walking on one of the flows. The water flowing to the left drops about 75 feet to the next series of flows. You really have to watch your footing around this place!

The river that runs through this canyon is composed entirely of run-off from the snow melt. As you can see, it produces lots of crystal clear water. I was tempted to remove the old socks and shoes and dangle my toes in the water just to see what it felt like until the shrill screams of a young girl who had just done the same thing convinced me that yes indeed, it's cold! This place contains many contrasts such as the jet black stone lava and the crystal clear white water.

Another picture of the stream flowing through Lava Canyon.

This next picture is of the largest drop in the falls - about 75 feet. Unfortunately, I did not manage to capture a person in this photo to assist with understanding the scale of this falls. It is quite large and very fast flowing.

This is the last leg of the Lava Canyon (at least the last leg that is easy to get to). There are all manner of trails in this area. Some are for beginners and some are for experts. I went as far as the suspension bridge which gives you a great view. However, beyond that point, the footing is treacherous and you better have the right type of hiking equipment (something better than tennis shoes). The stream is about 45 feet below me in this picture.

In this next photo, you can see the suspension bridge (yes, I walked across it). It bounces up and down (considerably) when you walk across it which adds to the excitement. If you look in the bottom right hand corner of the photo, you can see two people standing/sitting on one of the flows. That gives you some idea of the enormous scale of this area.

Ok, so I had to have proof that I was willing to cross the bridge. That's me, trying to look brave while keeping my knees from knocking.

This lava deposit really caught my eye. Presumably, many years ago, it was in contact with the water that has now etched its way down into the cliff beside it leaving this structure high and dry. The top granulated rock is similar in appearance to the pyroclastic flows emanating from Mount St. Helens in 1980. The underlying rock is more typical of a traditional lava flow which has a smooth appearance.

The walk to and from the canyon is beautiful. The forest is thick and composed of some very mature pines and furs. The first stage of the path has been paved to make it wheelchair accessible.

.

.

How do you capture a picture of a 200+ foot tree? Well, I tried to capture most of it but again there isn't really anything in this photo to give you an idea of the scale. Suffice to say that this tree had a trunk that was approximately 3.5 to 4 feet in diameter. On the north side of Mount St. Helens, trees like this were snapped off close to the ground as if they were simply toothpicks.

I guess I was waxing artistic in taking this photo. The way the sun was hitting this old bleached out tree trunk really caught my eye. Note, the healthy trees were considerably taller than this old relic. Still, even in death, it had a beauty all its own.

Heading North....

Having enjoyed my visit to the southeast corner of the mountain but wanting to be sure I saw the north side as well, I reluctantly left the Lava Canyon area and drove back along highway 503 to I-5. I then continued north about 25 miles and once again left I-5 on highway 504 and headed east toward the north side of the national monument. If you get the opportunity to visit this area, you should make a stop at the Cinedome visitor center on highway 504 (on the left, within one mile of I-5). They have a large screen video show that reveals many details concerning the May 18, 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption. They also have a good gift selection. I purchased the book titled "Road Guide to Mount St. Helens" by Robert and Barbara Decker. It is an excellent publication that will make your trip much more enjoyable. It is filled with facts and things to see along the roads to Mount St. Helens. See the footnote at the end of this web page for more information about ordering their publication. As they correctly point out in their book, to visit the Mount St. Helens National Monument and really explore its many areas can easily take three days. I wish I had been granted that much time on my visit but alas I was trying to work it in with my real purpose for being in Oregon; a business trip. I strongly encourage you to pick up a copy of this road guide and use it as you navigate your way into the monument. Also, go there early in the day! There is a nice visitor center called the "Mount St. Helens Visitor Center" maintained by the Forest Service located on the right hand side of the road just beyond the Cinedome. This center has a theater that shows a video concerning the history of Mount St. Helens and an exhibit about volcanos.

The next picture is typical of the healthy areas of the forest. Keep in mind later on that this is what the mountains immediately surrounding Mount St. Helens looked like prior to the May 18, 1980 eruption. Pine and fur trees (some of them extremely tall) cover most of the terrain. Grasses abound and small bushes and shrubs dot the landscape. There are a fair number of deciduous trees at the lower elevations.

Headed east into the park, this is one of the first views of the devastation to greet my eyes. Note that inside the boundaries of the monument, most of the trees were left in place in order to observe how nature would go about reclaiming its own. Outside the monument, mankind harvested many of the trees and planted new ones.

The Blow-down Region

In this photo you can see a large stand of trees on the mountain top that are still standing though stripped of all their branches. They are so far away they look like match sticks. The white "dots" on the ground are actually stumps of other trees that were broken loose at ground level and carried along with the blast cloud that enveloped this area. Keep in mind that these are huge trees with trunks that are about four feet in diameter. Again, when viewing this area, scale is everything. Look at the bottom center of the photo to see a car that was coming toward me. One unusual aspect of nature's recovery within the monument is the fact that in some areas, pine trees and shrubs have come back during the intervening twenty years while in other areas such as this one, very little plant growth has occurred.

This was my first view of the north side of Mount St. Helens. That's it straight ahead at the end of the highway in the clouds which makes it a bit difficult to see in this photo. Here you can get at least some idea of just how large a mountain it is (and was). In this picture, I am about 17 miles away from the mountain (line of sight). If you were to view the mountain from the air, you would find that it is horseshoe shaped with the opening of the horseshoe facing to the north (that's to the left in this photo since I'm headed east).

Mudflows

This is the mudflow that originated from Mount St. Helens and traveled as far as 75 miles away from the mountain. Although it looks like water in this photo (which was shot late in the evening with limited lighting available), it is a mix of dust, mud, gravel, and water from what used to be the North Fork Toutle River. In the distance you can see Mount St. Helens. The mudflows were caused during an eruption when the snowcaps on top of the volcano melted and mixed with the avalanche products to form a mud slurry. The mudflows also pick up additional moisture from rivers and water soaked avalanche debris. Much of this area would have been snow covered in May. Thus, when the hot contents from the eruption spilled out into the rivers and valley area surrounding Mount St. Helens, a great deal of water was liberated. This mudflow can be very thick. In the case of the Mount St. Helens mudflow, it carried hundreds of logs in the flow that acted as battering rams. Many homes (about 200) and bridges were washed away or buried in the flow. Seven hours after the eruption began, structures as far away as 30 miles from Mount St. Helens were buried under 20 to 30 feet of mud. The mudflow crested at Castle Rock and later flowed into the Columbia river blocking the shipping channel (it took six months of dredging before normal shipping was possible on the river again).

The picture below is a ground level view of the mudflow shown above. As you can see, it carried a lot of avalanche debris along with it such as trees, rock, etc.

This is another picture showing how the trees were simply snapped off at their base. A stump extending up about two to four feet at most was all that was left.

Remember the green forest I showed you earlier in the photo above? That's what this series of mountains would have looked like prior to the eruption. After the eruption, the hills were stripped bare of all vegetation (except for small plants and trees that were covered by snow). Of course, the melting snow contributed to the mudflows as well as protecting small flora and fauna.

I had wanted to make it to the Coldwater Ridge Visitor Center (about 7 miles from St. Helens) but unfortunately I ran short of time and it closed one minute before I could get there. So, I pushed on past Coldwater Ridge and arrived at Johnston Ridge (located 5.5 miles directly in front of St. Helens). This ridge was named for David Johnston; a geologist who had set up camp here to observe the volcanic activity at Mount St. Helens. Mr. Johnston had been studying the bulging north side of the mountain for several days. Unfortunately, the eruption that occurred at 8:32 AM on May 18, 1980, took his life as the blast from the volcano quickly engulfed his site burying him and his equipment under many feet of hot ash and avalanche material. He might have thought he would be safe since the ridge he occupied was some 1200 feet higher than the plains separating Mount St. Helens from his position and of course Mount St. Helens was 5.5 miles away! However, the force of the eruption surprised many people and pent up gas that was released by the avalanche produced a pyroclastic flow (mix of steam, carbon dioxide, rock particles and hot air) that raced along at speeds well in excess of 100 mph. As a result, this material rushed across the plain and up the sides of Johnston Ridge traveling 1200 feet up the side and over the top and even down the back side of the ridge. The picture below is of the back side of that ridge. The last words heard from Dave Johnston were from a radio transmission he generated at 8:33 AM in which he said "Vancouver, Vancouver, this is it!" His transmission was subsequently terminated.

In this photo, I have parked my car in the visitor center and I am looking at the back side of the ridge. As you can see many trees were literally ripped off of this mountain by the blast. Most of these tree stumps are in the 2.5 to 4 foot diameter range. This picture has an eerie resemblance to a grave yard with many markers shining in the sun. In a very real sense, that's just what they are.

Below - another view of this same ridge; the backside of Johnston Ridge. To the left you can see "Harry's Ridge" - named after another person who lost their life in the eruption. You can see many trees standing on Harry's Ridge. From this distance (about 2-3 miles away), they look like match sticks. Harry's Ridge was not actually close to Johnston Ridge - it's a photographic illusion as I was using the zoom capability of the camera to shoot a close-up of these stumps (in the foreground) which were about 3-4 feet in diameter. You aren't allowed to walk in the area beyond where I am standing as the United States Geologic Survey and National Parks organizations are studying all of the area within the national monument to see how nature reclaims itself. Stiff fines are in store for those who don't choose to obey the rules ($100 minimum the signs say). Still there is so much to see on the trails that it would seem a shame to deface this area by walking all over it. A sign there said that "plants grow by the inch and are destroyed by the foot."

This stump atop Johnston Ridge was as tall as I am (about 6 feet). Twenty years of wear and tear have definitely begun to decompose a lot of the stumps in this area but I suspect they will be around for many decades to come.

I didn't do it! OK, just kidding. Didn't want anyone to think I did this (the big hole in the ground behind me that is)! This was my first real view of the crater that is now Mount St. Helens. It is quite a contrast to the mountain that stood here prior to 1980. A friendly tourist asked me to take her picture and then thanked me by taking my picture. This is the viewing center atop Johnston Ridge. To the right of me in the photo is the viewing center. Unfortunately, it too was closed when I got there. If you go to the national monument, make sure you get there before 6:00 PM (Pacific time) so you can enjoy the visitor centers as well. I don't know if you can see it too very well in this photo but in the middle of the crater is a new lava dome. The dome grew in periodic episodes between 1980 and 1986. It is now approximately 1,000 feet tall and 3000 feet wide yet it looks so tiny inside the bulk of Mount St. Helens! The crater itself is 1 mile wide, a mile and one half long, and was originally 2000 feet deep (prior to the lava dome growing up in the middle of it). Some have estimated that in another 200 years, Mount St. Helens may be very close to its original height (assuming it does not experience another eruption similar to the one in 1980). The highest peak of the crater rim behind me is now at 8,365 feet in elevation. Try to visualize the mountain as it was pre May 18, 1980, with a typical peak at 9,677 feet! Imagine how much mass was displaced out of that cone!

Panorama Shot

This photograph is actually a combination of 4 photos. I wanted to try to capture the breathtaking view which extends from Harry's Ridge past the eastern pumice plain to Mount St. Helens to the avalanche flow and pumice plain in the west. There is actually a sizable gap between Harry's Ridge and the next mountain chain east of that (with Mount Margaret farther off in the distant background) but it is hard to see in this photo. Down inside that gap is Spirit Lake; an area that was completely overrun by the avalanche coming from Mount St. Helens. A gentleman by the name of Harry Truman who was the innkeeper for Spirit Lake Lodge, a quaint lodge nestled at the south edge of Spirit Lake, was killed when the huge avalanche buried his entire resort and caused the lake to rise above its banks by 200-250 feet! Also, the lake became 1 mile longer after the assault by the avalanche! Waves as high as 850 feet arose from the lake during the impact by the avalanche. Thus, Harry's Ridge was named in honor of Mr. Truman. Keep in mind that in this picture, the opening in the top of Mount St. Helens is approximately a mile wide. Using that as a scale, you can tell that Harry's ridge is about 4-5 miles away. I am standing 5.5 miles away from Mount St. Helens. During my exit from the monument, I found that the "blow-down" area in which trees were flattened, extended for some 17 miles line of sight from Mount St. Helens! Unfortunately, Spirit Lake was well within the blast zone and suffered the ravages of avalanche debris, ash, countless tons of organic material (trees, grasses, shrubs, etc.) and had its temperature raised to almost 100F. It was supposed that very likely no life would have survived within the lake. However, just recently a member of the USGS (U.S. Geological Survey) dropped a line into the lake just to see if anything would nibble at his bait and to his surprise he caught a 24 inch rainbow trout! They were elated! Of course the lake has been off limits to fishermen ever since the eruption but the USGS was extremely pleased to see that life had not only made its way back into the monument (herds of elk and deer, birds, burrowing animals, etc.) but some life had obviously managed to survive an incredibly devastating disaster. Note: you may have to scroll to the right with your browser window in order to see this entire panorama.

The Pumice Plain and the 'Pyroclastic Flow'

The area directly in front of the mountain in this photo is part of the pumice plain. In March of 1980, Mount St. Helens became active once again after sleeping for 123 years. Signs of activity included smoke coming from the top of the mountain and the deposition of ash material around the top of the mountain which blackened the mountain's otherwise white frosty top (snow). From March until that fateful day in May, the mountain continued to show signs of activity. The local authorities had warned everyone to evacuate the area but there were still those who either thought it would not happen soon or at least the damage would not carry as far as their location. They could not have been more mistaken. On May 18, 1980, David Johnston reported in from what is now Johnston Ridge (the location from which I took this photo) saying that the bulge that had formed on the northwest corner of the mountain was swelling at a steady rate. At 8:32 AM an earthquake measuring in at 5.1 on the Richter scale triggered a gigantic landslide and avalanche as the swollen side of the mountain came apart and cascaded down into the valley below. The avalanche traveled both to the east (toward Spirit Lake - to the left in this photo) and to the west (down the Toutle river - to the right in this photo). Although David Johnston was 5.1 miles away from Mount St. Helens, the combination of the avalanche and the pyroclastic flow combined to sweep over the mountain side he was occupying. When the avalanche material slid down the side of Mount St. Helens, the sudden release of the weight that was trapping the heated ground water and underlying magma resulted in a violent release of hot water that flashed to steam and released other gases. This turbulent and explosive force mixed with the rocky material of the mountain to form a blast cloud. The blast cloud traveled at a speed that exceeded that of the avalanche and has been estimated to have been traveling at speeds exceeding 100 mph. This flow was given the name "pyroclastic" flow from the words "pyro" meaning fire and "clastic" meaning broken. According to Robert and Barbara Decker's travel guide "A Pyroclastic flow is the most dangerous and most misunderstood of all volcanic features. It consists of a hot, denser than air mixture of rock fragments and gases - principally steam, carbon dioxide and heated air. This emulsion of solid particles and turbulent gases acts like a fluid, so a pyroclastic flow can pour down a steep slope at speeds exceeding 100 mph... About 20 pyroclastic flows swept out out of Mount St. Helens' crater during the afternoon of May 18, building up a plain of pumice deposits on top of the avalanche debris." Keep in mind that pyroclastic flows are really hot - as much as 1300F! The blast cloud that emanated from Mount St. Helens has been estimated to have attained speeds of as much as 200 to 700 mph! Imagine a black cloud coming toward you that is 500 to 1000 feet long, heated to approximately 500F, and moving at 200 mph! It was this cloud that ripped down and scorched forests for miles distant from Mount St. Helens. It climbed ridges and even descended into valleys carrying its destructive force to both the windward and the leeward sides of the mountains. I found that particular aspect of the destruction to be fascinating since I had originally reasoned that if you were located on the protected side (leeward side) of a mountain, you would be safe. In fact, there were no protected sides of the mountains that were caught in this blast. The only things that survived the blast were those that were buried under snow or in the ground.. At 14 miles distance from Mount St. Helens, the blast wind ceased knocking down trees but it continued to kill them by scorching them (due to the high temperature of the wind). Near the North Fork Ridge (one of the last locations where the blast force knocked down trees), there was a man named James Scymanky and three other loggers who were felling timber in the area. Mr. Scymanky described the approach of the blast cloud as "... a horrible crashing, crunching, grinding sound..." When the cloud hit his location, Mr. Scymanky was knocked down and could not see anything because of the extreme heat that engulfed him and the other three men. He remembers the terrible heat that engulfed him and made breathing almost impossible for 2 minutes. When finally visibility returned, all the trees in their working area had been knocked down flat and all four of the men were suffering badly from burns. Of the four, only Mr. Scymanky survived the experience. One other unusual and dangerous aspect of this destructive cloud was that the high dust particle content of the cloud caused it to produce frequent lightning.

By the way, the canals you see in these pictures range anywhere

from 20 feet to several hundred feet deep! They are about 2.5 miles away

from where I was standing.

The Avalanche Zone

This area immediately in front of Mount St. Helens reminded me of the moon; completely devoid of any signs of life and looking as though it had been scorched and sterilized. During the eruption this 'valley' was covered by 600 feet of avalanche debris which in turn was covered by more than 100 feet of pyroclastic flow deposits - the pumice plain. A six foot tall man would appear as just a speck in this photograph.

Harry's Ridge

This is another view of Harry's Ridge. As you can see from the picture below, it is littered with fallen tree trunks. From this distance, they simply look like match sticks. However, many of them are in the 3-4 foot diameter range and 100-200 feet long. A lot of the trees were carried over the hill into Spirit Lake which nestles below the back side of this ridge. The recovery phase of this area so very close to Mount St. Helens (relatively speaking) has been very slow. There are patches of green here and there but for the most part, there really is not a lot of plant growth to be seen. As you reach the 10-15 mile range of distance from Mount St. Helens you find that the forests have once again become green with the presence of small pine trees that are approximately 15-20 feet tall. Pine trees grow about one foot per year so these pines represent new growth since the eruption in 1980. None of that is seen in this picture however because this area was so close to Mount St. Helens. (This is the north end of Harry's Ridge).

Another view of Harry's Ridge (photo below - the southern end). This area received a great deal of the avalanche and pyroclastic flow deposits hence the rounded hummocks. The grooves have been carved subsequent to the eruption in 1980 by the run-off of snow melt and other ground waters.

I like this photo. I purposely framed it in such a manner as to capture Mount St. Helens in the background and one of its fallen victims in the foreground. This tree was quite large - its trunk was about 3 feet in diameter. As you can see, it has decayed considerably in the 20 years since it was originally toppled by the volcanic eruption. I call this photo 'Diary of a Murderer'. It seemed to fit. You can see the stump to which this tree was once attached in the lower left area of the picture. The stump was literally twisted off with many shards of wood sticking out in all directions. Some portions of the winds associated with the eruption allegedly reached 700 mph close to the volcano! This poor old tree, right atop Johnston Ridge, felt the full impact of that force!

This stump was on top of Johnston Ridge. It was caught in the worst portion of the initial blast.

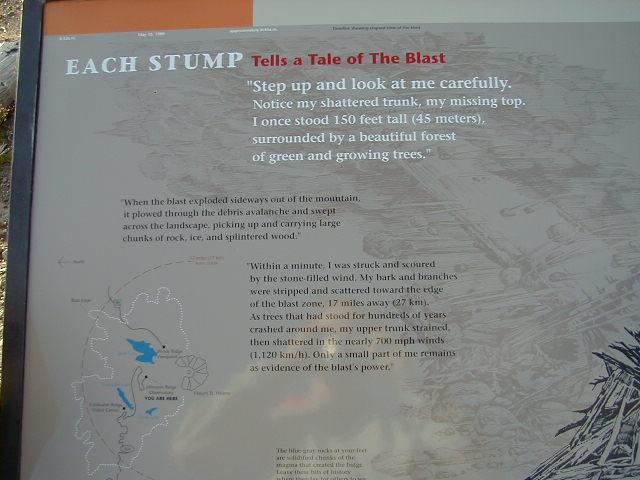

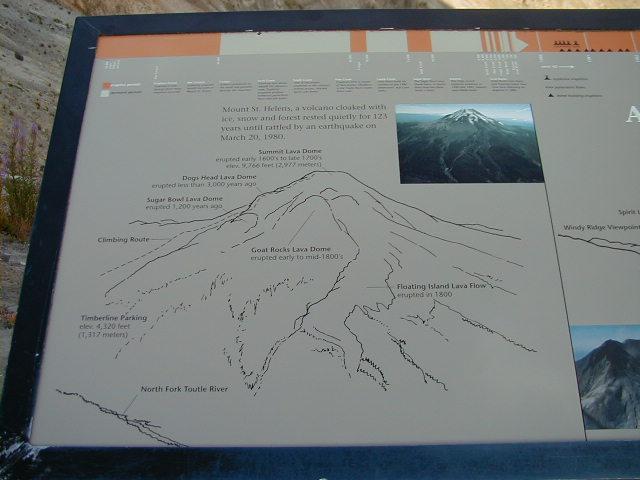

This poster on top of Johnston Ridge shows some of the history of Mount St. Helens - various lava domes have appeared in the past and erupted. There were several that occurred during the 1800s. Note the picture in the upper right corner. That's what Mount St. Helens looked like prior to May 1980.

An attempt to capture a picture of the lava dome inside the crater. Look closely in the center and you may be able to see some of the newly formed lava dome (new in that it was created since the eruption in 1980). Unfortunately, the sun was setting which reduced the direct lighting available to this area and visibility was also limited by considerable cloud content that was moving across the mountain. In 1992 the dome was approximately 1,000 feet tall and 3000 feet wide!

Pre May 18, 1980

(as viewed from Spirit Lake)

Post May 18, 1980

(as viewed from Johnston Ridge - about 2 miles west of Spirit Lake)

A Last Look

As I left the monument boundaries, I stopped to take one last photograph. This shot was taken late at night so please pardon the poor focus. You can see Mount St. Helens in the distance (about 12 miles away line of sight). The area that looks like a river is the mud flow that filled the former Toutle river and pumice, ash and avalanche material. If you forgot what it looks like up close, click on this link to go back to the close-up picture of the flow.

A Parting Word....

In summary, if you ever have the opportunity to visit the state of Washington, I hope you will take a couple of days to visit the Mount St. Helens National Monument. It is truly an awesome spectacle and it has an extensive history that is extremely interesting. It is sobering and humbling to view such a display of power and to try to embrace the scope of so great a disaster. Events of this magnitude come along infrequently within the passage of time and so it is a rare opportunity for us to observe both the destructive power of nature and the almost miraculous recovery of life against incredible odds.

St. Helens is a story of tragedy yes; there were 57 human lives lost here as well as the incredible loss of natural resources and animal life (est. 1500 elk and 5000 deer). However, it is also a story of recovery and hope. After five years, the animal population was back to normal for this area. Twenty years later many of the mountains surrounding St. Helens are looking green again thanks to the growth of 15-20 foot tall pine trees. The lakes that were thought to have been destroyed by the eruption have shown themselves to be resilient and have revealed hidden treasures of life. The old saying that life goes on is truly given meaning in this place.

It was getting late - around 6:30 PM. Most of the visitors to the Johnston Ridge visitor center had packed up their kids and cameras and were heading back home. I walked out along the desolate path of the hummock leading to Johnston Ridge - to the point closest to Mount St. Helens; probably very near the spot where David Johnston had stood on that fateful morning. Standing there alone in the midst of this enormous valley, I gazed upon and pondered the enormous girth of Mount St. Helens and the gaping crater that revealed the violent history of this mountain from May 18, 1980. I felt very small. I felt the enormity of a God who could create such a place and yet as powerful as this event was, it represented but a fraction of His own ability and power. As I stood there thinking about this place one last time before I too walked back to my car and headed for home, a verse from the Bible came to mind. It was:

Psalms 8:4 "What is man, that thou are mindful of him? and the son of man, that thou visitest him?"

For further information please see the following reference - an excellent publication for use when visiting the Mount St. Helens National Monument:

"Road Guide to Mount St. Helens" by Robert and Barbara Decker. Maps and Drawings by Rick Hazlett. ISBN: 0-9621019-6-6

Published by Double Decker Press, 4087 Silver Bar Road, Mariposa, California 95338